Taking away the protein cheat sheet

Computational models cheat, and you can tell that they're cheating by seeing where they look

Synopsis: By identifying where protein-ligand interaction models pay attention, we see ours trained on less data are likely memorizing proteins rather than wrestling with the structural contributions of individual amino acids. To discourage memorization, we increase protein diversity in our training sets, with a particular emphasis on small but functionally meaningful amino acid substitutions. We provide some evidence that this strategy is successful, and believe investment in protein diversity will be critical in making progress towards generalization of protein-ligand interaction predictions.

We recently took second place in the Evolved AIxBio Global Sprint Hackathon (ref 1). The hackathon granted contestants a week’s worth of Nvidia H100 GPU time, and we figured we could make good use of those resources to look more deeply at something that’s been bugging us over here. We are pretty paranoid about our models cheating in lots of different ways, and this was an opportunity to check on one of those ways. Before we get into the weeds, though, we should frame up the problem a little.

Can we tell if models are cheating, and can we use that information to help stop them from doing so?

There have been lots of interesting efforts to combine data and life science in the pursuit of understanding and improving human, agricultural, and ecological health. Other applications of AI/ML to challenging problems have often yielded stunning progress, and it has been easy to imagine a similar degree of progress in the life sciences is just around the corner. It hasn’t really happened yet, though!

One possible reason AI/ML in the life sciences hasn’t delivered is that models trained on life science data often cheat. They cheat on subtle signals from assay design, they cheat on the signature style of the scientists who envisioned the experiment, they cheat on variation in the tools and reagents and personnel used to generate the data. Models cheat all the time, because cheating is easier than learning physics or chemistry or biology or medicine.

Cheating AIs are pervasive

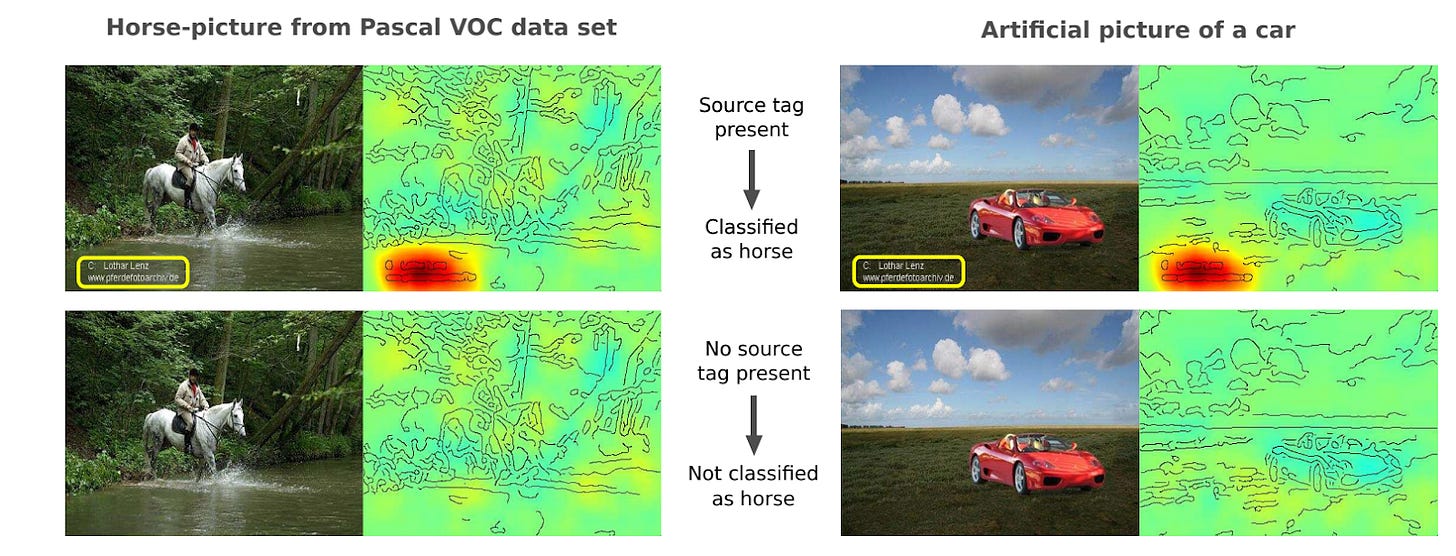

There are many classic examples of models cheating across a wide number of domains. One of our favorites we bring up now and again is models cheating on horse pictures from the PASCAL VOC 2007 image dataset (fig 1, dataset in ref 2, finding reported in ref 3). In the PASCAL VOC dataset, the researchers collected a number of images to train computers to identify 20 different objects captured by those images: person, bird, cat, cow, dog, horse, sheep, airplane, bicycle, boat, bus, car, motorcycle, train, bottle, chair, dining table, potted plant, sofa, or tv. About 20% of the horse pictures came from a commercial photographer who included a watermark in every image (here’s his instagram). Models learned to look for his watermark when shown horse pictures.

We know models looked for his watermark because we can tell where the models were looking to decide what was in the image (red blobs in fig 1). Researchers have put work into methods to identify where models are paying attention in order to get better explanations for model behavior (ref 4, ref 5). One approach is called an attention map; figure 1 shows such maps and what part of the image the model used to make its decision.

Figure 1. Attention maps suggest models trained on PASCAL VOC look for a photographer watermark when determining if an image contains a horse. Image adapted from ref 3, layer-wise relevance propagation (ref 4) was used to obtain the attention.

That the models are looking at the watermark and not anywhere else reveals a key flaw in the data collection. You want the model to learn what a horse looks like - the legs, the mane, the overall horse-ness of an image - and not just lazily find a very obvious watermark. If you improved your methods, maybe you could get the attention maps to look at the horse instead of the watermark, even if it were there. Since 20% of the horse images in PASCAL VOC had the watermark, it’s easy to think models might look for it first rather than wrestling with horse-ness. But what if you got many more horse pictures without the watermark, so only 1% of them had it? Or 0.01%? Would the models learn what horses really look like instead?

We had a similar problem with our protein-ligand interaction (PLI) prediction model.

Leash’s model to predict protein-ligand interactions was trained on our internal data

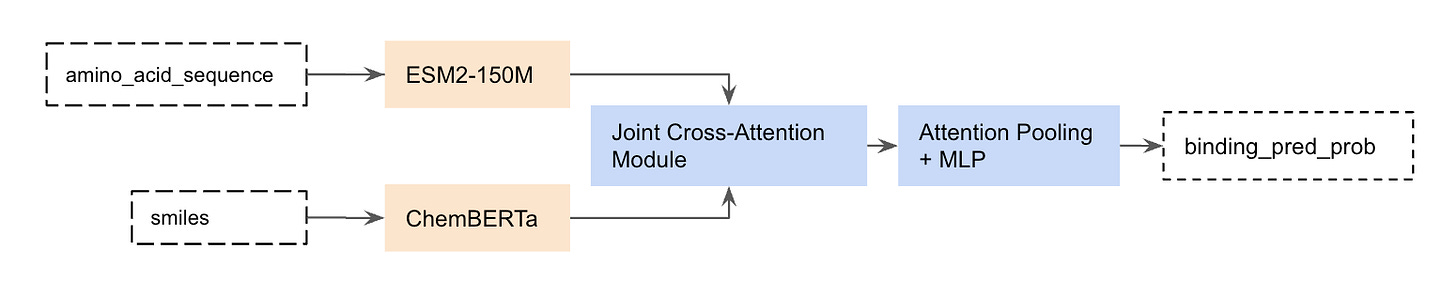

One of Leash’s goals is to get better at predicting if a given small molecule binds a given protein target. We recently announced Hermes (ref 5), our lightweight PLI binding prediction model which is competitive with state-of-the-art binding prediction models like Boltz-2. The Hermes architecture is really simple: it leverages pre-trained protein and chemical embedding models ESM2 (ref 6) and ChemBERTa (ref 7), on top of which a freshly initialized cross-attention and attention-pooling module learns to predict binding likelihood from trunk embeddings.

For non-ML people, this means that we took models that had rough understandings of what proteins look like or what small molecules/ligands look like and tied them together (fig 2).

Figure 2. Hermes architecture.

Hermes is special because it is trained exclusively on our chemical data: a massive corpus of PLI data generated here at Leash. We trained Hermes on hundreds of proteins screened against a proprietary 6.5M member molecule library, resulting in a dense map of PLI data that we think is ideal for training models without a lot of the problems you find in publicly available PLI data like ChemBL or BindingDB.

For the Evolve hackathon we explored how Hermes understands proteins, and tested out one of our key strategies for fighting memorization.

How does Hermes understand proteins?

We don’t force Hermes to think of the 3D physics of PLIs through design choices (by contrast, AlphaFold-like approaches do this using things like triangle attention). This leads us to wonder how exactly Hermes is able to effectively rank binders and non-binders: we don’t expect Hermes’ learned logic to involve an internal virtual protein-folding and ligand-docking simulation. The prevailing hypothesis here at Leash is that Hermes learns a simple mechanism for identifying proteins in the training set and derives some conception of their binding pockets through many examples of ligands that do and don’t stick to it. We suspect this sorta-cheating strategy should work due to a relative lack of protein diversity in our PLI dataset (hundreds of proteins is still very much a lack of diversity in our opinion).

Reading Hermes’ thoughts

To understand Hermes better, we need to visualize which amino acid residues are most important to its predictions. The model architecture includes a pooling layer where per-residue token representations are aggregated into a single representation vector using an attention-pooling mechanism. This mechanism involves assigning a scalar value to each residue in the protein controlling how much weight that token receives in the pooled representation. We can interpret these weights as a proxy for how important each residue is in determining the model’s final prediction, which is, in effect, an attention map that tells us which amino acids the model is looking at. Folks have started to use attention maps on the chemistry side (ref 9), but we haven’t seen as much of this for proteins.

For non-ML people, this means we can generate an attention map on the proteins Hermes is predicting on. We can tell which amino acid residues are receiving the most attention, and which ones tend to be ignored. If Hermes really understands binding, it should be focused on pockets. If Hermes is just memorizing proteins (like a horse watermark), then it probably focuses on unique strings of residues rather than conserved protein domains that include pockets. If cheating, Hermes might look for a handful of unique amino acids, identify the protein, and then remember other times it’s seen that protein.

What are protein domains?

Across evolutionary time, it’s common for chunks of proteins to get good at a particular function (say, putting a phosphate group on a protein, in the case of kinases) and then for that chunk to get duplicated and reused in other proteins for a similar purpose but maybe a different context (say, putting that phosphorylation protein chunk in a different kinase so it recognizes different targets to put phosphates on). These chunks or domains - functional units, really - tend to look pretty similar across the different proteins containing them, and so those chunks are conserved domains. There is a whole field of study in biology devoted towards discovering and identifying these functional units, and we leveraged that work to identify the domains here (via InterPro). Bits of the protein outside of those chunks can often be under less sequence constraint, meaning they could look less similar across proteins but unique to a particular protein.

The upshot of this is that for many proteins the conserved domain is the part that’s easily druggable because it’s functional (this is also why drugs can affect the behavior of multiple targets, and why drug selectivity can be so challenging), but regions outside those domains are more likely to be unique. If we think Hermes understands druggable pockets, it should look at the domains doing the enzymatic activity, but if we think Hermes is just memorizing protein ID, it should look at those unique regions outside the domains.

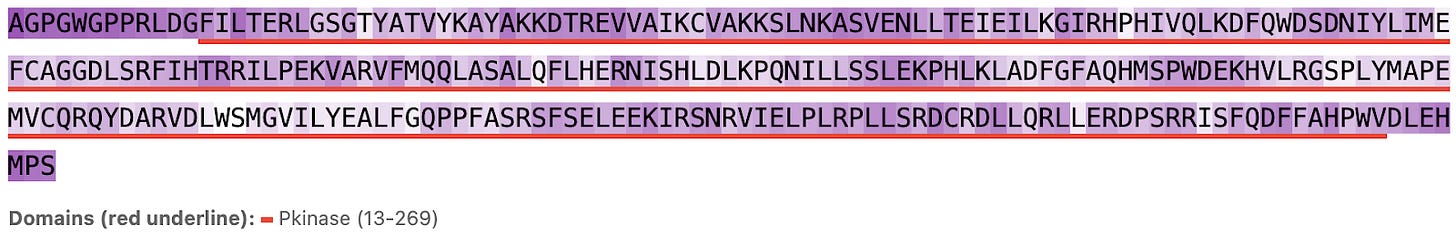

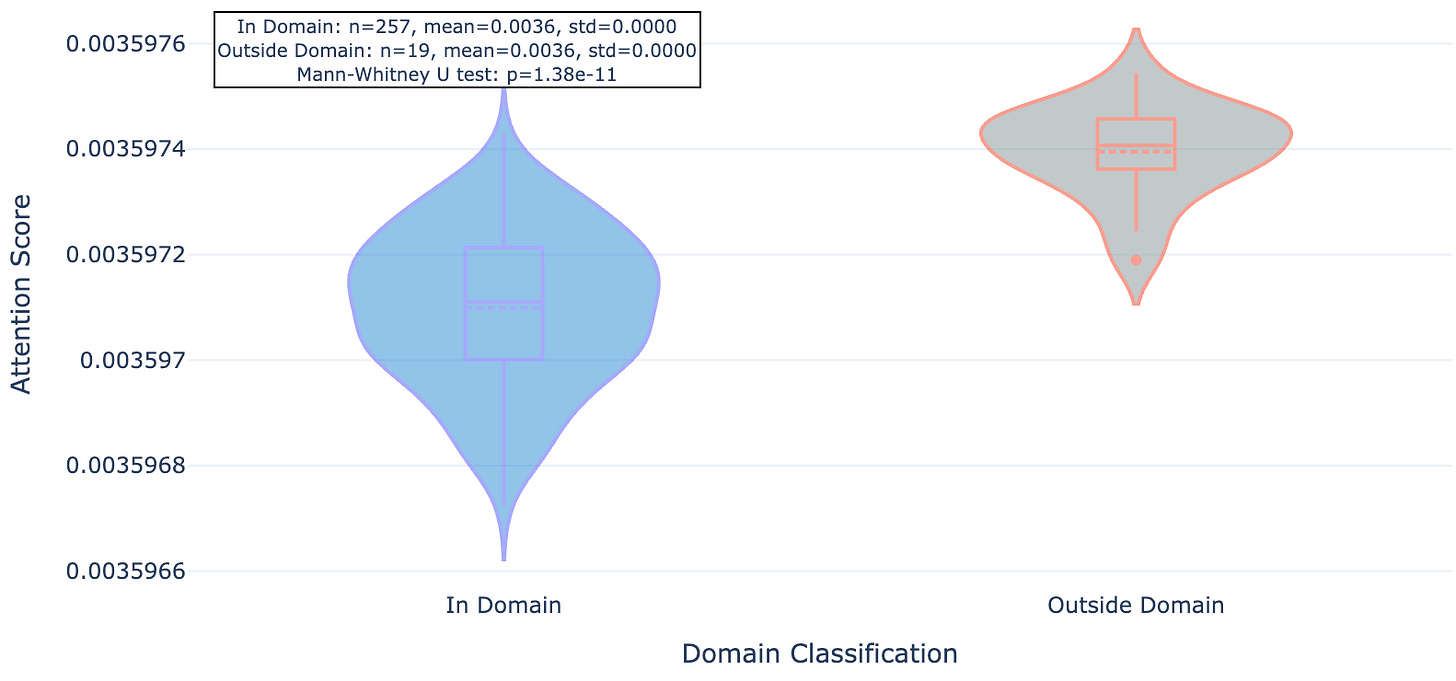

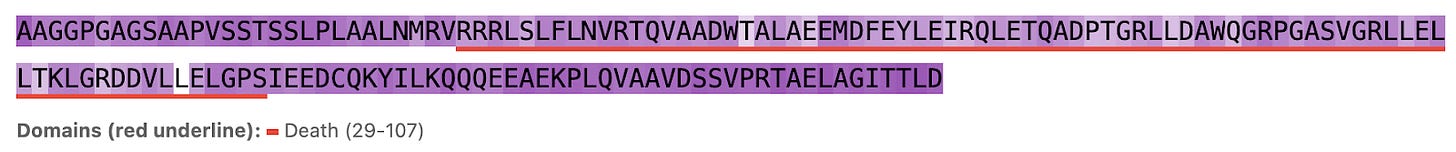

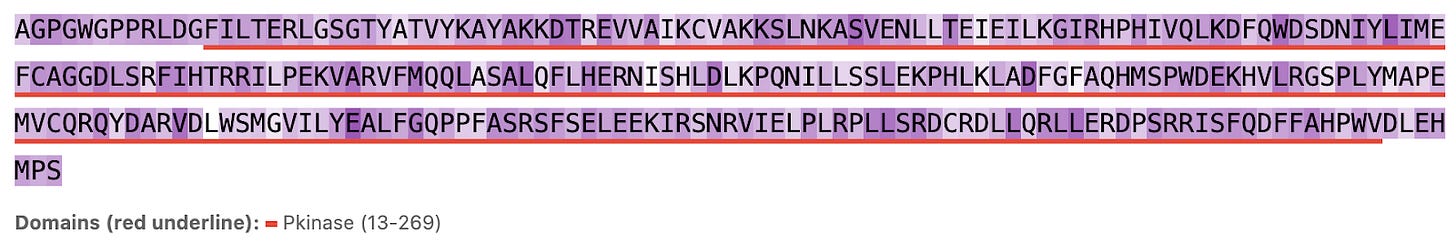

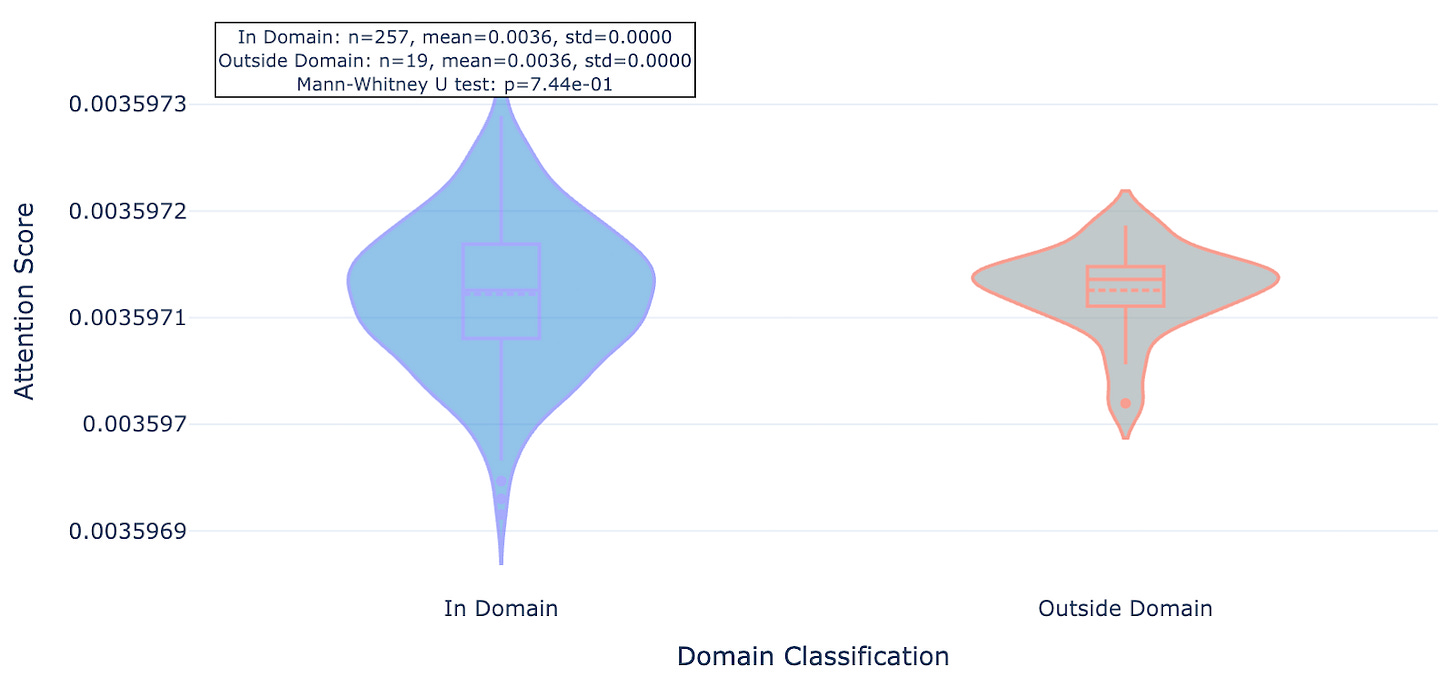

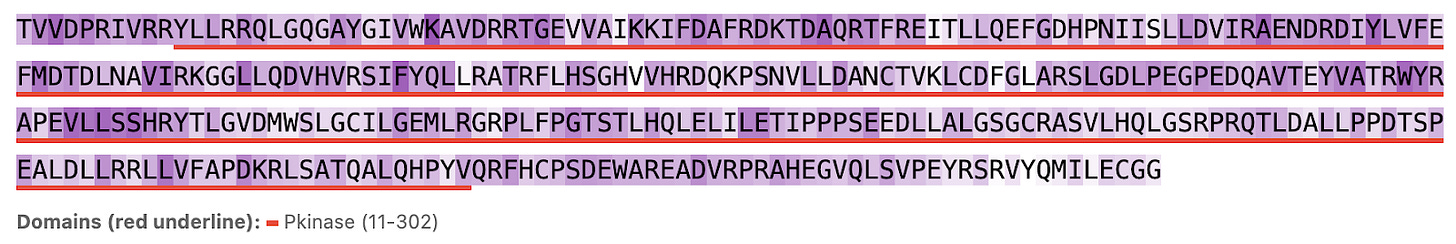

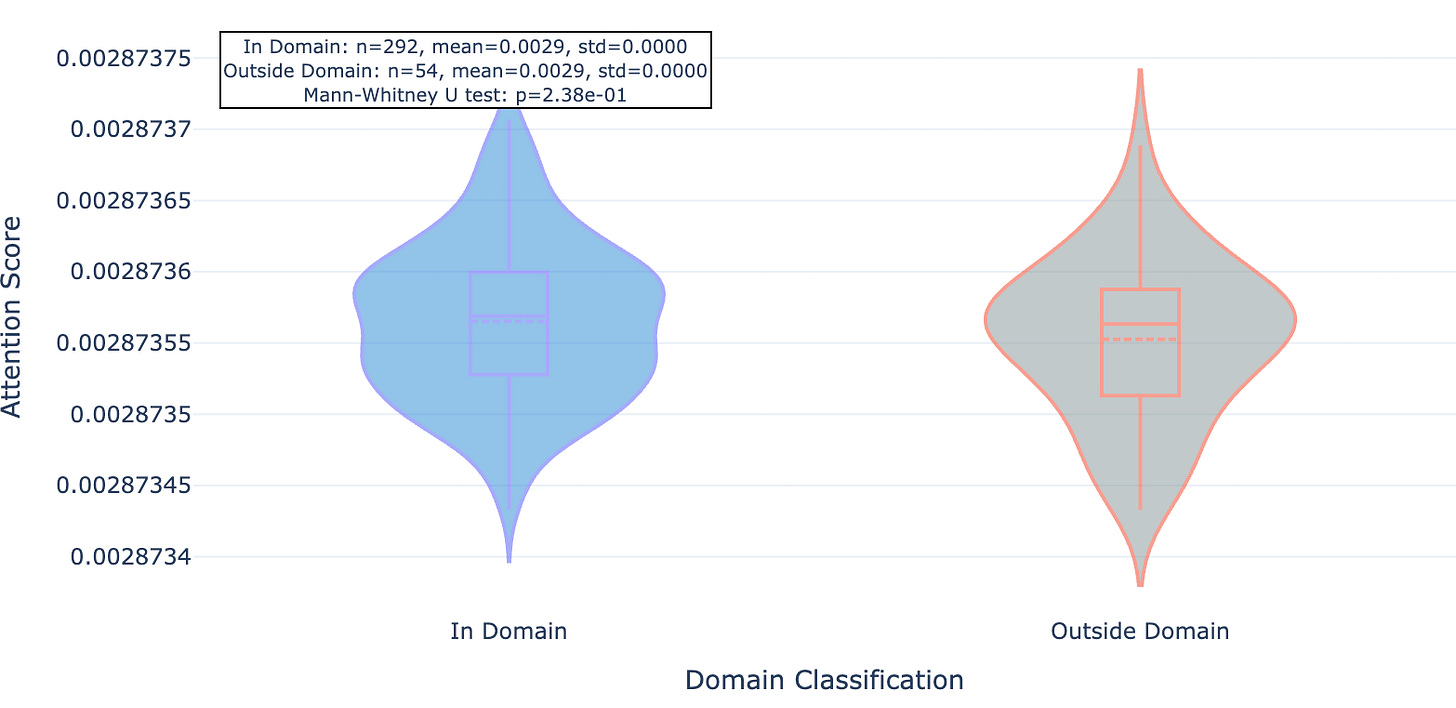

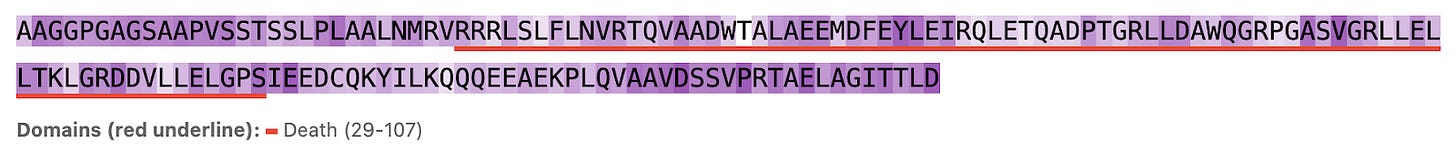

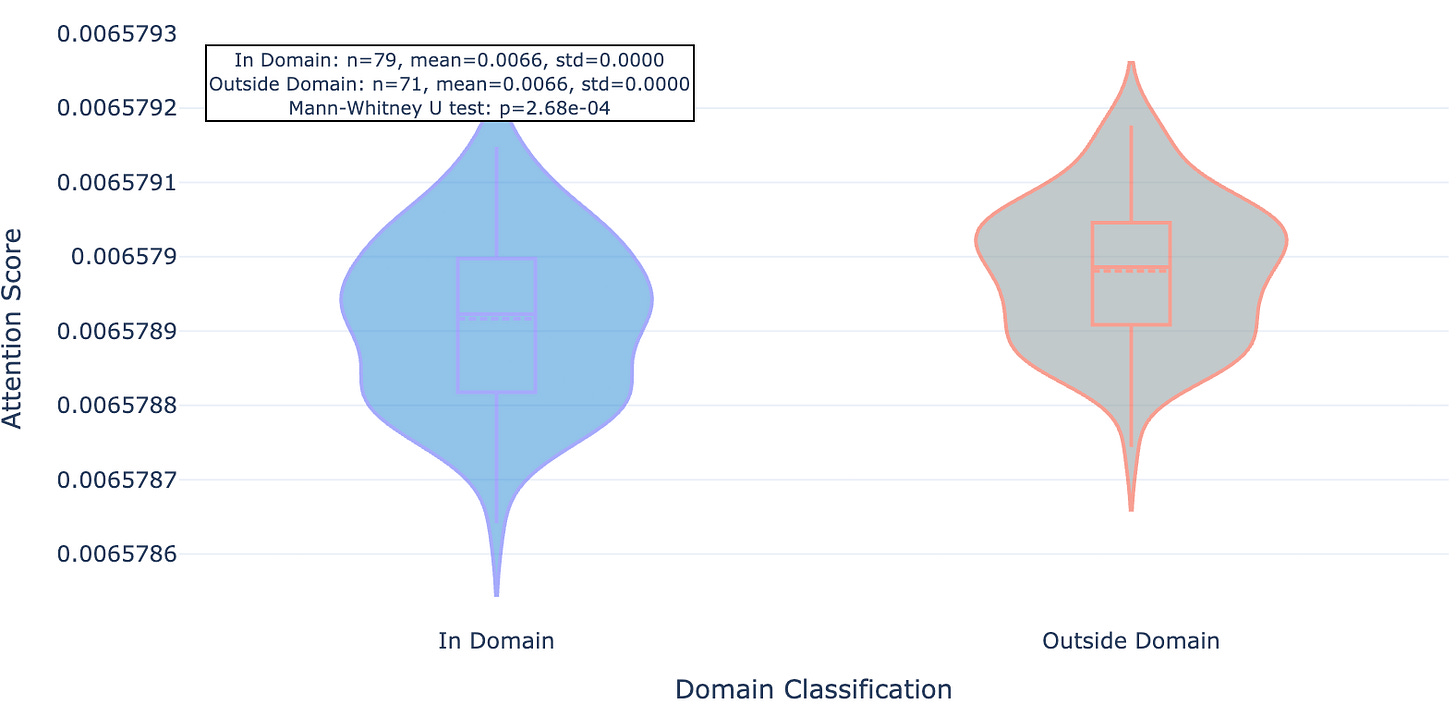

So does Hermes look at the functional part of the protein (conserved domains, underlined in red) or unique strings (less conserved outside domains)? Seems like the latter: residues within domains see less attention (lighter purple) while those outside see more (darker purple, see figures 3, 4, and 5). We show 3 proteins here (ULK3, MAPK15, and MYD88).

Figure 3a. ULK3 per-residue Hermes attention (darker background indicates larger attention values).

Figure 3b. ULK3 residue attention inside and outside conserved protein domains.

Figure 4a. MAPK15 per-residue Hermes attention.

Figure 4b. MAKP15 residue attention inside and outside conserved protein domains.

Figure 5a. MYD88 per-residue attention.

Figure 5b. MYD88 residue attention inside and outside conserved protein domains.

As you can see for these three targets, and indeed the majority of 20 targets evaluated, Hermes has a distinct preference for attending to residues outside of conserved domains.

Challenging the model through targeted sequence mutations

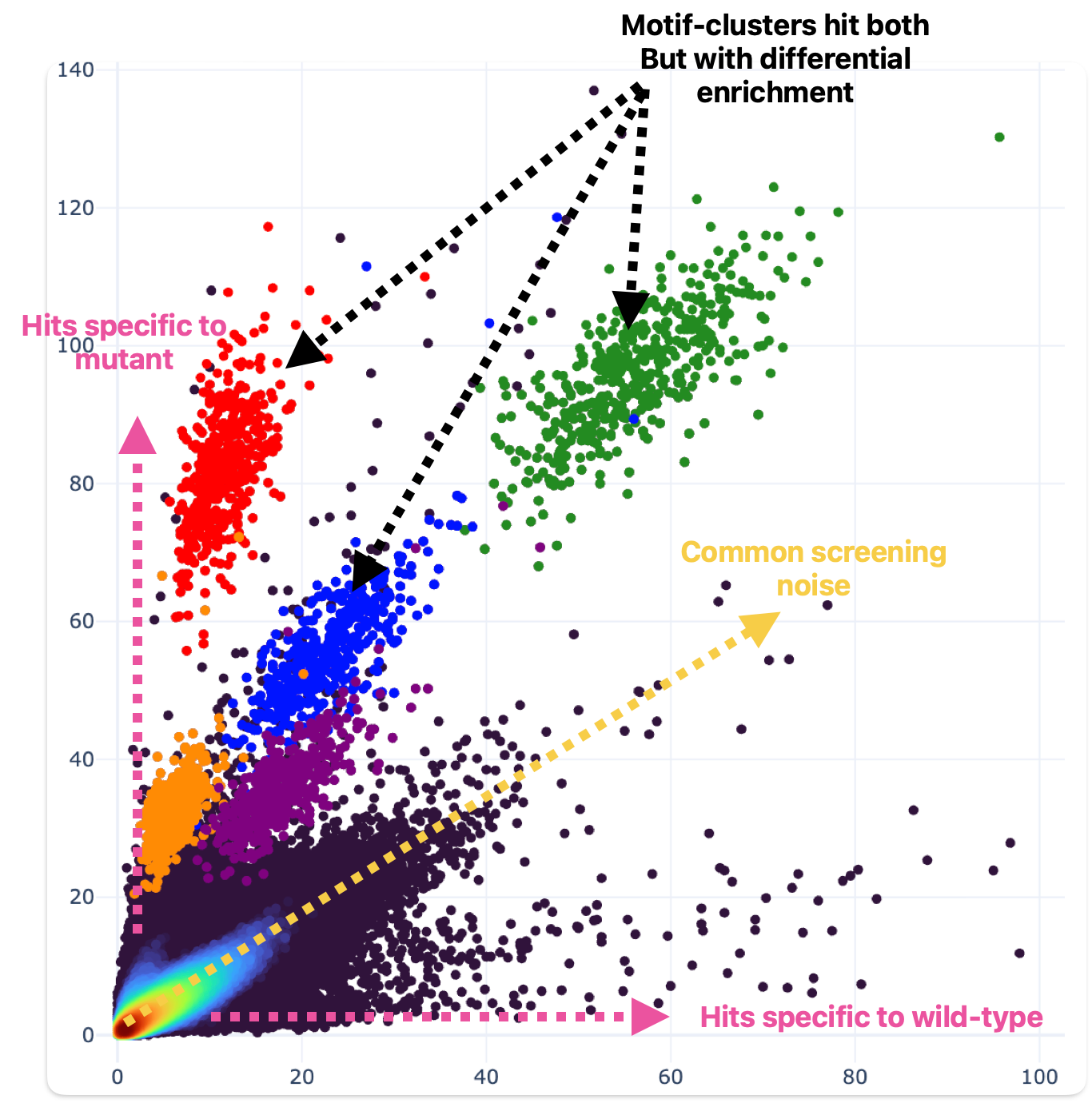

We can synthesize and screen many proteins really fast, like 100 a week. Recently we’ve used this capacity to generate challenging training data using targeted sequence mutations. The idea is that we can change the hit signatures of proteins by selectively mutating their amino acid sequences that drive ligand binding (fig 6).

Figure 6. Single amino acid substitutions can drive dramatic effects in ligand binding behavior. One residue was mutated relative to wild-type (wild-type hit enrichment on the X axis; mutant hit enrichment on the Y axis). Motif clusters differ by a single building block.

This data challenges the model to understand how changes to amino acid sequence within the critical structural domains of the protein targets impact binding.

To be very explicit: if you change one amino acid, the rest of the protein is identical (>99%), but the binding behavior can be completely different (fig 6). That means identifying the unique protein is no longer sufficient to predict binding. We hoped that after enough of this challenging training data is presented, the model can’t just get by memorizing proteins but instead will have to grapple with individual amino acid contributions to binding behavior.

The new model looks more at the domains

We used our Evolve hackathon compute to train new Hermes models on datasets containing this new mutant data and repeated our residue attention analysis on these new models. Here are those same plots from a model trained on the harder task.

Figure 7a. ULK3 per-residue attention paid by mutant-trained Hermes.

Figure 7b. ULK3 residue attention inside and outside conserved protein domains paid by mutant-trained Hermes.

Figure 8a. MAPK15 per-residue attention paid by mutant-trained Hermes.

Figure 8b. MAPK15 residue attention inside and outside conserved protein domains paid by mutant-trained Hermes.

Figure 9a. MYD88 per-residue attention paid by mutant-trained Hermes.

Figure 9b. MYD88 residue attention inside and outside conserved protein domains paid by mutant-trained Hermes.

We found that this newer model whose training set included the mutant data and about 40% more “standard” Leash data seemed to pay significantly less attention to residues outside of conserved domains, an effect that was consistent across the 20 proteins observed.

Protein variation is probably going to help

We didn’t go hog-wild on this analysis - it was a week-long hackathon, after all - but it does suggest our hunch about Hermes memorizing proteins when given a limited training set is on the right track. In particular we suspect more single amino acid substitutions of functional consequence are likely to help models learn, say, when a particular residue contributes a hydrogen bonding event to a number of similar chemical series. Recent work with cofolding models (Boltz-1, Chai-1, AlphaFold3, RosettaFold All-Atom) and simulating such substitutions suggests that none of the models have an understanding of local residue effects but instead memorize wild-type pockets (ref 8, fig 10). Such models tend to be heavily structure-based, which means they’ve been trained on a lot of PDB cocrystal structures, and there’s not a lot of structures in the PDB that have mutations like these (or incentive to make them!) to test their effects on ligand binding.

Figure 10. When confronted with missing pockets, cofolding models put the ligands in the same place anyway. Image modified from ref 8.

If protein variation is probably going to help, then we should get more of it

A nice thing about the high-throughput protein production engine we’ve built here at Leash is that it enables us to collect exactly this sort of data. Combining large numbers of protein variants with large numbers of chemical variants allows us to discourage our models from memorizing. It might get us closer to teaching our models that this residue in this pocket encourages this chemical motif to bind there, rather than simply memorizing protein ID and recalling chemical motifs from the training set.

We started Leash on the premise that protein-ligand interaction prediction problem needed more data, and that includes dense sampling across the distribution of the space. This necessarily requires protein variation, and we look forward to seeing how more of it contributes to progress in drug discovery and the life sciences.

We thank the whole Leash team: Andrew Blevins, Sean Francis-Lyon, Brayden Halverson, Sarah Hugo, Edward Kraft, Ben Miller, and Mackenzie Roman, for their Herculean contributions to the data and its analysis.

Really clever approach to diagnosing model cheating through attention maps. The shift from non-conserved regions to functional domains after mutant training is kinda brilliant evidence that data diversity forces better learning. Most teams optimize for more data volume when quality and variance might matter way more. Single amino acid substitutions as an anti-memorization stragey feels underappreciated in the field.

Great article! As a relative layman in protein science, I found this article to be really interesting and easy to follow!