Data contamination is all random forest needs

Here's why we believe our Hermes prediction results are real

Earlier this month we described Hermes, a simple model trained on massive amounts of physical measurements that we’ve generated here at Leash: Hermes achieves state-of-the-art performance on predicting whether a given small molecule might bind to a given target. We argued this by showing Hermes predictions across a large number of small molecules that are known to be binders or known to be not-binders to specific protein targets.

To convince ourselves that our improvements in performance were true, we had to tackle two issues that plague machine learning efforts in a general sense:

How do you evaluate model performance in the first place?

How do you guard against cheating?

This post is about how we considered these issues. Most of it is about the second one.

How do you evaluate model performance?

More precisely, how did we evaluate Hermes performance here at Leash?

To figure out if Hermes was any good, we used it to predict binding or not-binding to specific targets using a bunch of physically-tested examples. Some of them we generated ourselves; others came from an aggregation of work by the biotech community that was already public. We took these two sets, and then asked the models we built and models others built to predict them. Results are in fig 1, taken from the original post.

The public data

We described our public data strategy in the Hermes post and reproduce that description below.

Papyrus is a subset of ChEMBL and curated for ML purposes (link). We subsetted it further and binarized labels for binding prediction. In brief, we constructed a ~20k-sample validation set by selecting up to 125 binders per protein plus an even number of negatives for the ~100 human targets with the most binders, binarizing by mean pChEMBL (>7 as binders, <5 as non-binders), and excluding ambiguous cases to ensure high-confidence, balanced labels and protein diversity. Our subset of Papyrus, which we call the Papyrus Public Validation Set, is available here for others to use as a benchmark. It’s composed of 95 proteins, 11675 binders, and 8992 negatives.

Papyrus is a fairly straightforward, cleaned-up dataset with a certain amount of diversity. We put this set together in an afternoon, and it’s already public, so we had no issue immediately releasing it.

Leash private data

We also put together a validation set from data we collected on our platform. It’s 71 proteins, 7,515 small molecule binders, and 7,515 negatives. Our chemical libraries aren’t public, which means this validation set isn’t public, either. That means nobody else can use it to evaluate model performance. (We are very aware of this and working to fix it.)

So why did we make the private validation set in the first place? To guard against cheating.

How do you guard against cheating?

Machine learning types often will have a big dataset of examples of the thing they’re trying to model, and they’ll split it into a bunch of examples they show the model (“train”) and some others they hide and then ask the model to predict once they think it’s done learning (“test” or “val”). This is pretty easy to do with, say, pictures of horses or whatever. If you have a lot of pictures of horses at different distances and lighting conditions and coat colors and you never have the same picture in test and train for the models to memorize, you feel better about the model’s ability to identify a horse in a picture. But if you have the same picture in train and test, the model can just memorize the picture and not grapple with things like noses and legs and overall horse-ness of the image.

We needed to test the performance of Hermes and compare it to other models, and so we needed to put together some validation sets to do that. First, let’s talk about the public set.

A good split for us isn’t good for everyone

With Hermes, we only trained on Leash data. Leash molecules don’t look anything like the molecules in public data (our Papryus subset). Chemical space is huge, and we designed our internal chemical libraries ourselves, so we didn’t expect them to look anything like molecules made and tested by a bunch of other folks who then put them in the public domain. (We checked to be sure, see fig 4 in the main Hermes blog post). This approach afforded us a pretty good test-train split for the Hermes model.

When comparing against Boltz-2 performance on Papyrus, though, we had a problem. Boltz-2 was trained on public data (link) (including CheMBL, which Papryus is directly extracted from), and so asking Boltz-2 to predict on data it’s already seen is allowing Boltz-2 to cheat. Boltz-2 has fine performance on Papyrus, but maybe that shouldn’t surprise us, since it was probably cheating!

Even if there’s no direct overlap between molecules in public training and testing sets that allows for memorization, there are more insidious ways models can cheat off of public data. Maybe specific molecule types or attachment chemistries are beloved by a researcher, and that researcher only submits binders to public databases. Your model might learn to recognize the attachment chemistry, use that to identify the researcher, and conclude all molecules that look that way are hits when in fact they are not.

Molecules that have seen a lot of refinement are also likely to be hits - researchers refining them were expecting as much - and models might learn from public sets that bells and whistles on those molecules are markers of activity when they’re really not. These are biases that are the result of human choices, and training and testing on biased data might just lead your models to memorize bias. Synthetic negatives are also the result of human choices and susceptible to bias. Cleaning the data will not solve this problem.

We believe these public datasets are biased in lots of ways. That led us to create our own validation sets, which we hoped would have less bias.

How do you split a big group of molecules?

We were lucky to have an obvious split between molecules designed by Leash and molecules in the public domain, but then we couldn’t really make an honest comparison with models that themselves were trained on public data. What’s a good way to make an honest comparison? We made a new validation set by splitting molecules from Leash so that the validation set is far away from what Hermes was trained on, and also far away from the public data that other models were trained on. Splitting our Leash molecule collection was trickier than just separating different horse pictures.

Why? Biological activities of chemicals might be driven by parts of the chemical, and those parts could be memorized instead of learned. Here’s what computational chemistry sage Pat Walters had to say about it:

[ML] teams often opt for a simple random split [between test and train], arbitrarily assigning a portion of the dataset (usually 70-80%) as the training set and the rest (20-30%) as the test set. As many have pointed out, this basic splitting strategy often leads to an overly optimistic evaluation of the model's performance. With random splitting, it's common for the test set to contain molecules that closely resemble those in the training set.

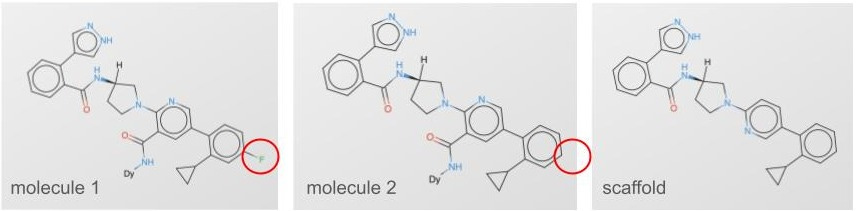

Pat goes on to show a couple different ways of splitting the data that have greater or lesser functional overlap between the splits, and the farther away your test is from your train, the more honest your evaluation. Beyond random splitting, there’s scaffold splitting (fig 2). You can see both molecule 1 and 2 are very similar, and they share a scaffold. You do a scaffold split, and those molecules either end in only train or only test.

Scaffold splitting isn’t the only way to do things. So what’s the best way to split those molecules? For us, we leveraged the combinatorial nature of our DNA-encoded chemical libraries (fig 3).

DELs are great for splitting

DNA-encoded chemical libraries are a core technology we use here at Leash (read the BELKA results post if you’re unfamiliar). One great thing about them is they enable multiple levels of splitting, and we can use those levels to check how our models behave.

We could split randomly, which runs the risk of memorization like Walters cautions against above.

We could split on scaffold, which in theory parses between similarity, but might not be enough.

Because DELs are made of building blocks, we could then titrate out the number of building blocks shared between test and train. Do we share 2 out of 3? 1 out of 3? 0 out of 3?

Building blocks themselves can have profound similarities or dissimilarities. As we think about 3) above, we could split not just on building blocks but on whole clusters of building blocks, so no similar building blocks are shared at all (fig 2, fig 3).

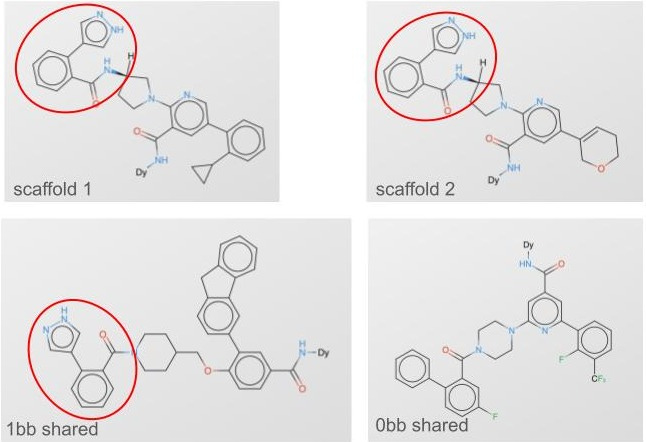

Our Leash private validation set is this last category: it’s made of molecules that share no building blocks with any molecules in our training set, and also the training set doesn’t have any molecules containing building blocks that cluster with validation set building blocks. It’s rigorous and devastating: splitting our data this way means our training corpus is roughly ⅓ of what would be if we didn’t do a split at all (0.7 of bb1*0.7 of bb2*0.7 of bb3 = 0.343). The clusters look like fig 4: we reused the colors in this plot so don’t overindex on them, there are about 200 building block clusters that we used to keep our splits honest.

In exchange for losing all that training data, we now have a nice validation set where we can be more confident that our models aren’t memorizing, and we can use it to make an honest comparison to other models that have been trained on public data. And in that comparison, we do very very well (fig 1).

Different splits have different difficulty levels

If you squint at figures 2 and 3 you can start to get a sense of how similar or different molecules can be, and then you can start to think about what might happen if they both behave similarly but one is trained on and the other is used in validation. You could split randomly and your model could memorize. You could split on scaffold and your model could memorize. If a single building block is driving the binding, you could have only 1 building block shared and your model could memorize. You could even have one building block sharing the same cluster as another building block and your model could still memorize!

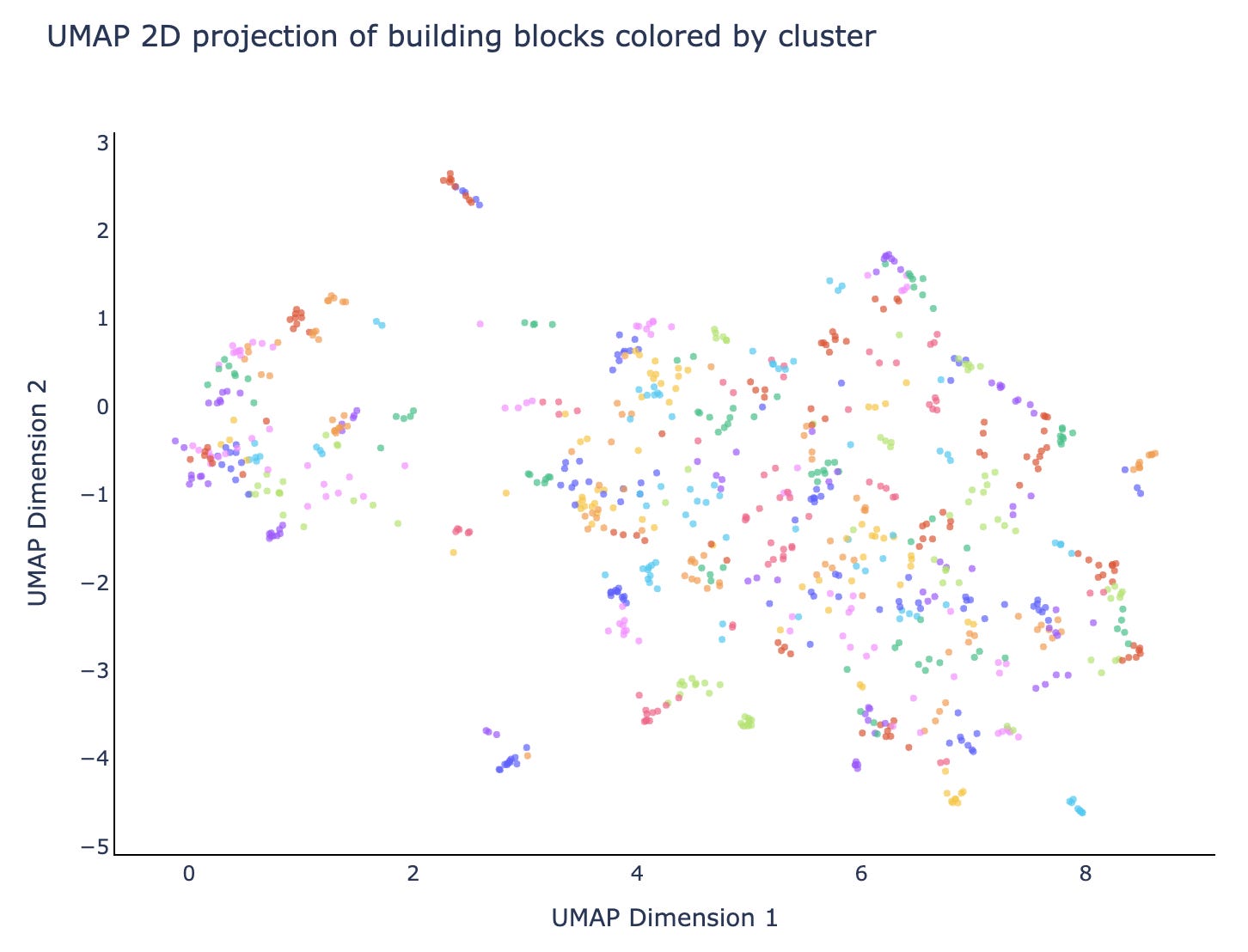

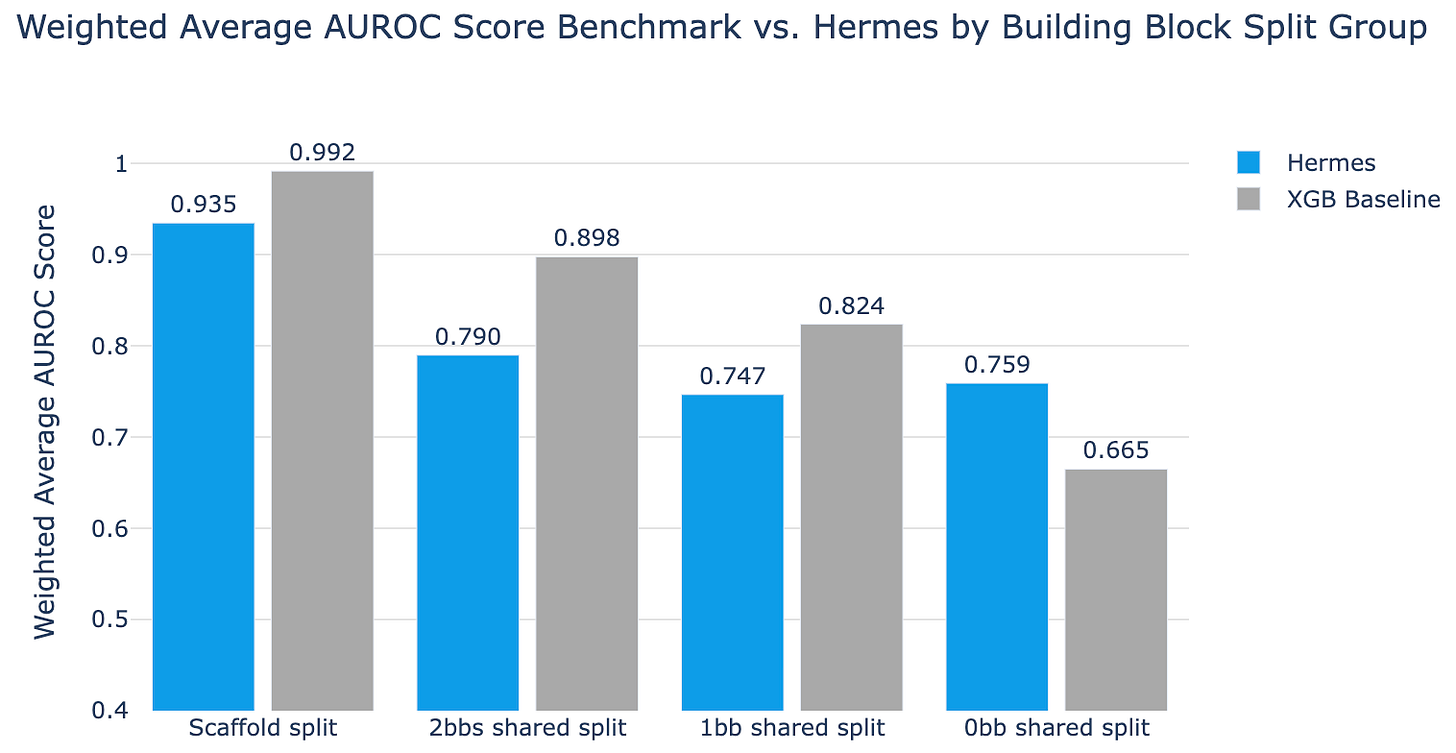

To get a feel for this, we ran all these splits against Hermes (a simple model but still a transformer) and XGBoost (a super-duper simple baseline). As you look at fig 5, you can see that XGBoost outperforms Hermes until the task gets very very difficult. (XGBoost is a great baseline model to evaluate if a given fancy approach is really performing well; we’d like to see folks compare new approaches to it as much as possible.)

Note that only with the 0bb_shared split do we see Hermes beating XGBoost. As the task gets harder, tree-based XGBoost can no longer overfit on similarities between test and validation sets, while Hermes maintains performance. This is a conscious tradeoff we made to limit Hermes’ ability to overfit and memorize, which we think leads to more generalization. We believe this approach drives Hermes to learn useful things.

The secret beauty of DELs for model training

A chemical library made up of discrete building blocks and simple attachment chemistries doesn’t just allow us to employ really nice test-train split strategies. In other machine learning tasks, one trick to boost performance is to go out and get examples of so-called “hard negatives”. For a classification model, these are examples that the model thinks are positives but are in fact negatives. These examples are close to the thing you’re trying to classify, and they confuse the model.

We want to be able to draw a line between molecules that are binders and molecules that are not, and we have to draw that line in a complicated, high-dimensional space. Our intuition is that by showing the model repeated examples of very similar molecules - molecules that may differ only by a single building block - it can start to figure out what parts of those molecules drive binding. So our training sets are intentionally stacked with many examples of very similar molecules but with some of them binding and some of them not binding.

These are examples of “Structure-activity relationships”, or SAR, in small molecules. A common chemist trope that illustrates this phenomena is the “magic methyl” (link), which is a tiny chemical group (-CH3). Magic methyls are often reported to make profound changes to a drug candidate’s behavior when added; it’s easy to imagine that new greasy group poking out in a way that precludes a drug candidate from binding to a pocket. Remove the methyl, the candidate binds well.

DELs are full of repeated examples of this: they have many molecules with repeated motifs and small changes, and sometimes those changes affect binding and sometimes they don’t. We really want to leverage this special structure of our chemical libraries in selecting training examples as well as using it to build effective splits.

You want to be able to discriminate between close neighbors

Chemical space is really huge, like 10^60. But also, a typical HTS screen has a hit rate of 0.1-1%. Does this mean that in all of chemical space there are 10^57 binders to your target?

Probably not!

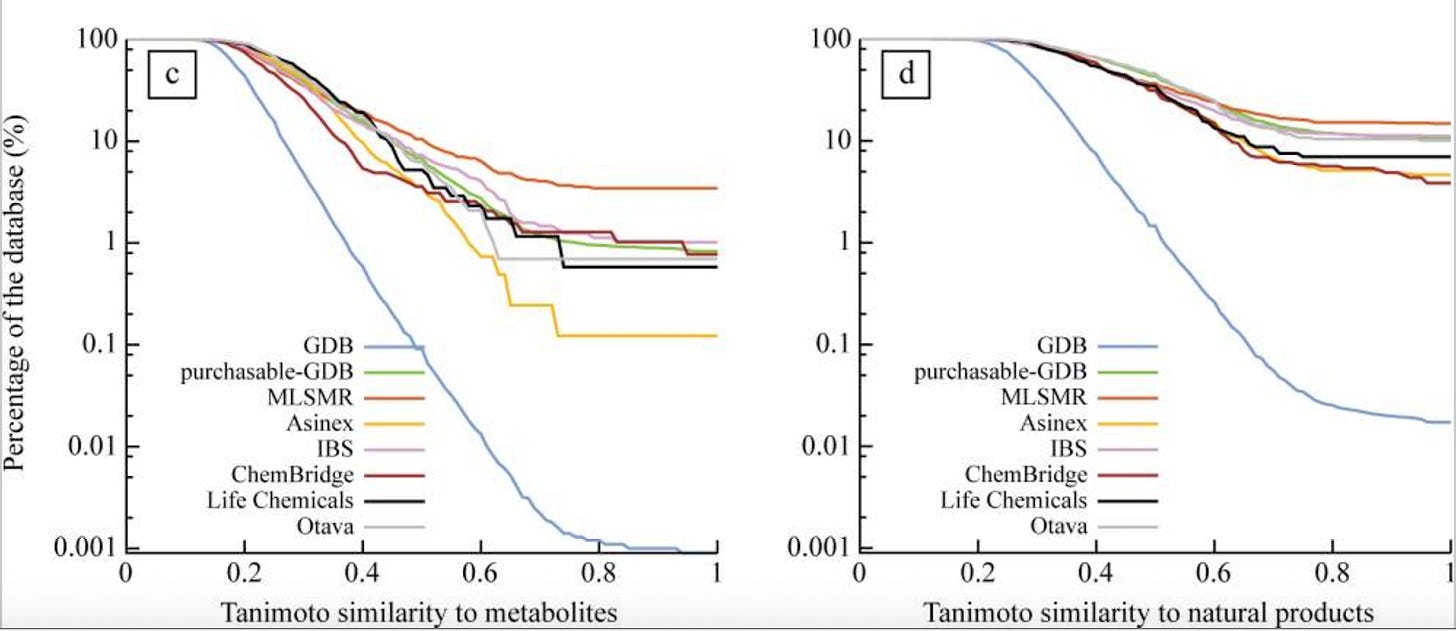

Chemical space is unevenly distributed with regards to biological activities. Commercial chemical libraries look a lot more like metabolites than they would by chance, because human beings selected them (fig 6, link).

We have a lot of not-hits in our DELs, like 99%. But most might come from a corner of chemical space that never provides any hits. Our models could memorize those corners and still not be very good at understanding the subtle H-bond interactions and pi-stacking that lead to binding. If we were randomly selecting not-hits, the best we might ever do is to learn about those corners.

But DELs afford us the opportunity to get close not-binders and really interrogate those structures. And because we screen all of our targets (>600 and counting) against the same molecules (6.5M and counting), we have repeated examples of chemical motifs that bind in some proteins and don’t bind in others.

We believe this density of data, and the repeated examples of very similar molecules, are the real secret sauce to driving our model performance. It’s only possible with DELs, and even then it’s only possible by screening at the scale we screen here.

In the next post, we’ll examine the protein side of things. Stay tuned!

Do you plan on posting any PR AUC or precision metrics? AU ROC is great but when we have millions of samples with 1000 true binders the model can predict all as non-binders and have 100% accuracy. Seeing how Hermes does on your data where the metric is PR AUC or precision would tell a much better story, in my opinion. Also, any thoughts on using datasets with a higher ligand to protein ratio? Your private set has an average of 212 ligands per target (15,030/71). Some datasets have 50k+ ligands and only 200 true binders. The numbers seem slightly inflated here.